Form Follows Function…with a Caveat

Posted on April 10, 2019

It was a perfect day for the dog show. Breed judging was at 9:00 AM. Not too early and it would be finished before it got warm. Competition was strong with a five point major in bitches. The judge was a well known judge with good breed knowledge and a reputation as an impartial judge.

The winner’s bitch class was a strong one with 4 bitches that could finish with this win. One owner was counting on the win. When she went reserve, she politely asked the judge why he put up the other bitch. “She had a better head,” he said.

The exhibitor thanked the judge and politely left the ring, but when she got to the setup, the hissy fit started.

“What was that judge thinking?? Doesn’t he know that form follows function? They don’t move on their heads!!”

We frequently hear those kinds of statements at ringside. I’ve heard that exact phrase several times … and at different breed rings.

Yes, form follows function. Every breed was originally bred for a purpose. All were developed for helping man find game, herd flocks, guard flocks, guard people, draft, kill rodents, and many other practical purposes. Yes, even toy breeds have a purpose … pleasing their owners.

When man developed breeds it was for survival. The appearance was far less important than their ability to do a specific job. Did they really care how a dog looked as long as it could hunt, herd, guard, or do whatever their job was? Probably not. They were looking for tonight’s supper, or worried about their herd, or concerned about protection.

If function is the only criterion, then why don’t today’s judges reward solely on the dog’s ability to function in the manner required for the original purpose? Simple … we changed the rules. We added a caveat.

In the early development of working field dog breeds, the breeders used best performing available dog and the best performing available bitch in hopes of producing superior working dogs. In many cases they were successful, so they repeated the process often by in-breeding (though the didn’t know what in-breeding was). Eventually they had the dogs that they wanted and often times they looked similar.

As the later breeders began honing their skills at producing good working dogs, they began to favor well performing dogs that were pleasing to the eye.

Many of the breeds that were the forerunners of dog shows were hunting dogs. The British were among the first to have Pointers with outstanding hunting characteristics, sound movement, and that were similar in appearance. They earned a reputation world wide as being the best bird dogs to be found.

It is said that one of the reasons for the start of dog shows was because the English Pointer became famous worldwide for their ability to deliver the goods when hunting. Setters were in a similar situation. Top prices were offered for those dogs from buyers in many countries, and not unexpectedly, there were some unscrupulous breeders that would capitalize on this demand. Some dogs were shipped to overseas buyers as “English Pointers” that were sorely disappointing. There was little recourse for the buyer.

It followed that buyers of dogs that were sold as sight-unseen needed some manner of assurance that they were buying the real deal.

Good British breeders decided that one way to assure consistent quality was to develop a standard for the well-bred British dogs and to breed to that standard. The breed standards were written to describe not only the functional characteristics of the breed, but also the aesthetic qualities.

Quality could be assured if there was a competition judged by impartial third parties. The best dogs were rewarded prizes, and so began dog shows.

The first dog show was held on June 28, 1859 in the town of Newcastle, U.K. Only Pointers and Setters participated in this show. Guns were awarded to the winners, which became the norm at subsequent shows. Thus the name “Gun Dog Group” used by the British for what we call our “Sporting Group.”

In 1860, hounds began to be shown. Dog shows increased in popularity as more breeds were allowed entry and as dog showing became a sport for everyone. Shows were new and many issues needed to be resolved.

Most important of all were the criteria for judging. This question had arisen at the very first show in Newcastle in 1859, when sporting dogs were assessed on their look and shape, rather than their abilities in the field. Indeed, there were complaints throughout the Victorian period that the quality of English sporting dogs was in decline because breeders looked for “a good neck, bones and feet”, rather than “intelligence, a good nose and stamina”.

Form Follows Function!

Does this sound familiar … over 150 years later??

True, but we added the unspoken caveat “Form follows Function … as long as it looks as the standard requires.”

Form follows function does not fully describe how a breed looks. Form follows function merely tell us what anatomical features are essential to make it a sound moving animal, of the right temperament, and with any special functional requirements, such as size or coat.

Let’s look at a couple of examples.

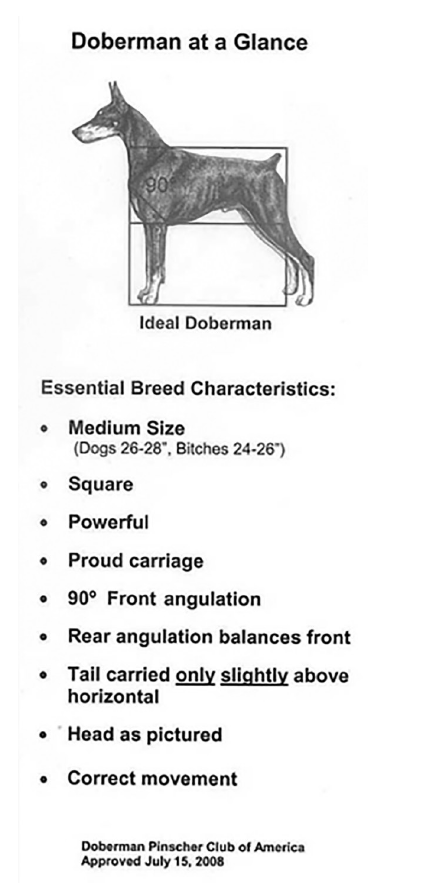

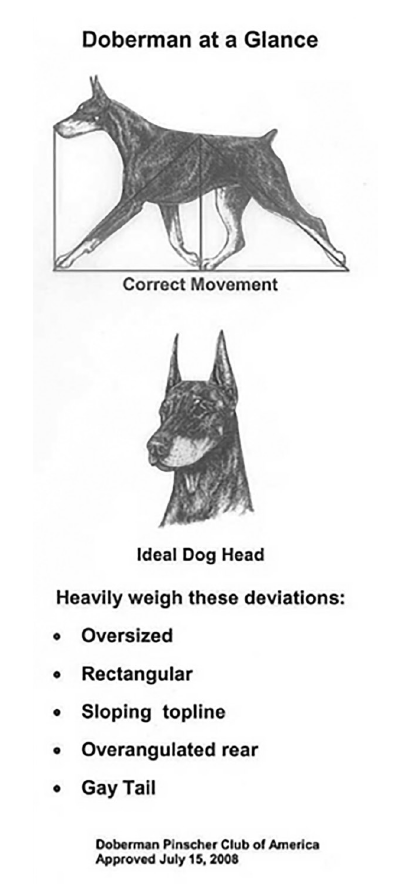

We have a Doberman that is square, equal leg length to body depth, correct topline and tailset, with angulation exactly as described in the standard. He moves soundly with good reach and drive. His head is a blunt wedge with equal length and parallel planes. He is energetic, obedient, and brave. His temperament is the perfect blend of protection when required and calm friendliness with children and non-threatening adults.

He has no tan markings. The form is correct for the function, but not for the show ring. There is the caveat.

Then there is the Rottweiler that has the perfect outline, with good substance, correct proportions and angulation, correct head, sound moving, and strong in character. Everything you want in a draft/protection animal.

He’s red. He has the correct form for function, but not for the show ring. There is the caveat.

What is vital in form follows function? There are many breeds that do similar jobs, but are completely different in appearance. Some of the dogs that do similar jobs were developed in different countries with different terrain and climate, but they all sprang from the best performing available stock in the region of origin. The precursors to the breeds may have had the right working skills, but a different head, or different color, or even a different overall profile.

So does “Form Follows Function” really define a breed. Partially, but not fully.

The breed must be built right and have the exact appearance as that described in their standard in order to do their jobs.

Come now, does a guard dog have to look exactly like a Doberman to be a good guard dog? Can’t a Bullmastiff or Rottweiler with the right temperament do the job? Or heaven forbid, couldn’t a cross breed of these dogs be perfectly suitable as a guard dog? After all, much of a guard dog’s success depends on temperament, not just anatomy, color, and head type. Look at the Belgian Malinois, the most often used working breed in the military and law enforcement. They don’t look like other guard breeds, but their form is obviously correct or they wouldn’t be so customarily used.

Come now, does a guard dog have to look exactly like a Doberman to be a good guard dog? Can’t a Bullmastiff or Rottweiler with the right temperament do the job? Or heaven forbid, couldn’t a cross breed of these dogs be perfectly suitable as a guard dog? After all, much of a guard dog’s success depends on temperament, not just anatomy, color, and head type. Look at the Belgian Malinois, the most often used working breed in the military and law enforcement. They don’t look like other guard breeds, but their form is obviously correct or they wouldn’t be so customarily used.

How about herding dogs? Many of them do a similar job, albeit sometimes in different environments and with different stock being herded. Couldn’t cross breeds that have the right temperament and are sound in body and movement be just as effective? Yes, but with purebred dogs, the breed also has to appear as the standard describes. The caveat still applies. “Form follows Function … as long as it looks as the standard requires.”

A good illustration of the adage “Form Follows Function” can be found in sporting breeds. Go to a field trial or hunt test and consider how those dogs might fare in the show ring. Many of them are far from good representatives of their breed. Some may be nearly unrecognizable as the breed, but they may be hunting machines. That’s because the field dogs are bred first for performance with far less regard for breed type. They hold “Form Follows Function” as the primary criterion in breeding.

Sometimes, even with pure bred show dogs, a decision will be made with more emphasis on “breed type” … what the dog looks like, rather than on function.

I recall a judging assignment where I was put in exactly that situation. I was judging Samoyeds in China. Most of the exhibits were less than satisfactory with the exception of one. One dog had all of the essentials that are required for an excellent Sammy. But there was a problem. This dog was cow hocked. The standard clearly states that cow hocks are a serious fault in this breed. I was stuck. Form follows function or breed type. I swallowed hard and put up the cow hocked dog considering all of the other virtues he had.

After the show was over, the exhibitors were offered the opportunity ask questions of the western judges. I was specifically asked to describe the correct rear on a Sammy. I knew what they were thinking and I told them that I recognized the dog that won was cow hocked and that I knew it was a serious fault. Then I asked them if they knew the most serious fault that a dog can have. None offered an answer so I told them that the worst fault a dog can have is lack of virtues. I suggested that they consider this in their future breeding programs. It would be better to take your best functioning bitch to this cow hocked dog to gain some of the virtues that were missing in your breeding stock. Then keep the most anatomically correct puppies with the best breed type and begin correcting the one serious fault, while gaining some of the virtues that were lacking.

The next time you hear that often quoted “Form Follows Function,” please remember that only describes some of the key components of breed, but not all of them.

Bob Vandiver is a past Chairman of the DPCA Judges Ed Committee and current member. He has been approved to judge since 1996 and approved for all breeds in the Working, Sporting, Herding and Non-Sporting Groups.